On the Incarnation: Chapter One

Good morning, everyone!

I’m going to start posting something new on the blog here. I’ve wanted to start writing again for a while, and this is a good excuse to do it. A few Sundays ago, I quoted Athanasius’ most famous work, “On the Incarnation of the Word,” and got some quizzical looks. Let’s remedy that!

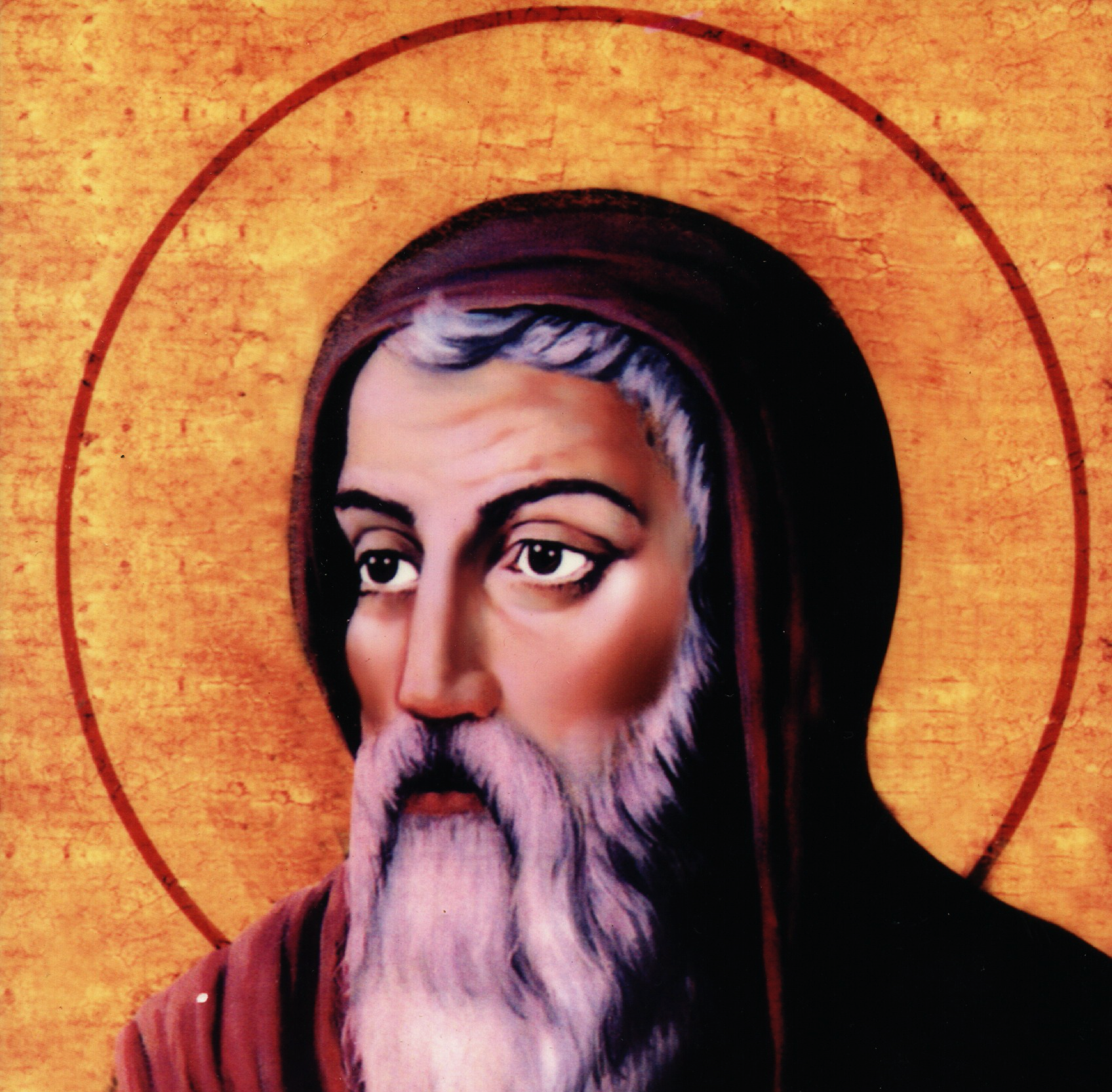

Athanasius is an early church father who is probably responsible for most of the way you process the incarnation of Jesus Christ. You may not know his name, but we are theologically indebted to him. His writing is ancient, so you can find a copy of On the Incarnation easily in multiple places on the internet. I’m going to be reading it in small chunks and just posting my thoughts on it as I go. Don’t think of this as another installment of the Stapleton Baptist Book Club; I’m not going to have a set schedule. I’m just going to write as I read and think, and you can join in with me by talking to me in the comments.

Today we’re going to look at chapter one. It should be fairly short and sweet, I think: chapter one is the introduction. But Athanasius uses it to explain what he’s trying to do.

The book is written to a dear friend of Athanasius named Macarius. It’s written as a follow-up to another book that we’re not going to worry about right now. In introducing the topic for discussion, Athanasius spends a paragraph or two discussing with Macarius the intellectual response Jews and Greeks have to the core Christian claim, namely that God himself has taken on a human nature and come to dwell among us here on earth.

According to Athanasius, the Jews “calumniate” the doctrine of the incarnation, which means “utter maliciously false statements, charges, or imputations,” or to “injure the reputation.” This may sound antisemitic, but pump the brakes on that. To consider oneself a Jew (as opposed to a Messianic Jew or a Christian, neither of which are in view here) is to make a religious statement. After the first advent of Jesus, continuing in Old Testament Judaism necessarily entails a denial of Jesus being the Christ. To accept Jesus as the Christ would move one into the Messianic Jewish or Christian camp (Messianic Jews are just Jews who recognize Jesus as the Messiah and possess saving faith in him…they’re Christians, but they use the term “Messianic Jew” to maintain connection to their heritage). Jews who continue to deny Jesus is the Christ do calumniate his incarnation. They don’t believe it happened, and the thought of it is offensive to them.

Athanasius also said the Greeks “deride” the incarnation. “Deride” means “to laugh at contemptuously.” Greek thinkers thought of the incarnation as a silly doctrine. There could be multiple reasons for this. First, why would a god become a human? Not just take human form, mind you, but actually become a real human? Humility was not a Greek virtue, and that’s not an insult; it literally wasn’t. They didn’t think humility was a good thing, and for a god to become a man would be the height (depth?) of humiliation. There was also the gnostic-ish belief that spiritual existence was more pure and good than physical existence. Why would a god who exists spiritually by nature dirty himself by being subjected to the griminess of physicality on earth? It just didn’t make sense to the Greek mind.

Christians, however, “venerate” the doctrine of the incarnation. We see it and marvel. We see it and are driven to worship. Athanasius saw the incarnation as further proof of God’s “godness.” He took something the Jews believed to be impossible and did it anyway. He took something the Greeks thought to be unseemly or silly and made it beautiful and Divine. He won the greatest battle in the cosmos by becoming the least. And because he became the least, one day all will recognize him as the greatest. It’s quite the whirlwind of wonder.

But then at the end of chapter one, having established that Jesus did take on flesh, Athansius asks the million-dollar question: why? He didn’t want Macarius to be ignorant of the reason Jesus took on flesh, and we shouldn’t want to be ignorant either. If God was going to save us, there was only one way to do it, and it required the Word becoming flesh and dwelling among us. The second person of the trinity does not, by nature, have a physical body, but he had to take one upon himself if he was going to win salvation for us. In short, Athanasius’ reason for why the Word became flesh was this: God wanted to save us and there was no other way to do it.

There’s one transitional paragraph at the end of chapter one: our next stop is an examination of God’s initial act of creation. In Athanasius’ mind, salvation in Christ is a “re-creation,” a making new of something that has been damaged or corrupted. Since the first creation was created by God through the Word, it only makes sense that the re-creation would be accomplished by him through the same Word.

Thoughts? Let’s hear them in the comments! You’ll get chapter two…soon? Maybe? Likely. See you then!

More in Stapleton Baptist Blog

January 20, 2021

On the Incarnation: Chapter TwoJanuary 19, 2021

On the Incarnation: Chapter OneMay 19, 2020

Pilgrim's Progress: Chapter Eleven

Leave a Comment

Comments for this post have been disabled.